- Chinese

- French

- German

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Russian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Arabic

- Irish

- Greek

- Turkish

- Italian

- Danish

- Romanian

- Indonesian

- Czech

- Afrikaans

- Swedish

- Polish

- Basque

- Catalan

- Esperanto

- Hindi

- Lao

- Albanian

- Amharic

- Armenian

- Azerbaijani

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Cebuano

- Chichewa

- Corsican

- Croatian

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Frisian

- Galician

- Georgian

- Gujarati

- Haitian

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hmong

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Igbo

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Kazakh

- Khmer

- Kurdish

- Kyrgyz

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Luxembou..

- Macedonian

- Malagasy

- Malay

- Malayalam

- Maltese

- Maori

- Marathi

- Mongolian

- Burmese

- Nepali

- Norwegian

- Pashto

- Persian

- Punjabi

- Serbian

- Sesotho

- Sinhala

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Somali

- Samoan

- Scots Gaelic

- Shona

- Sindhi

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Tajik

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Welsh

- Xhosa

- Yiddish

- Yoruba

- Zulu

- Kinyarwanda

- Tatar

- Oriya

- Turkmen

- Uyghur

Pure refined coal tar: eco-friendly applications?

2026-02-21

You see ‘pure refined coal tar’ and ‘eco-friendly’ in the same sentence, and your first instinct might be to scoff. I get it. For decades, coal tar’s legacy has been tied to heavy industry, PAHs, and environmental remediation headaches. But that reflexive dismissal misses the nuance of what ‘refined’ actually means in an industrial context today, and where the material science has quietly pushed the boundaries. It’s not about greenwashing an old product; it’s about asking if a highly processed derivative, when applied with precision and full lifecycle control, can fit into modern sustainability frameworks. The answer isn’t a simple yes or no—it’s a series of ‘it depends’ based on application, substitution logic, and waste stream management. Let’s unpack that.

The Refinement Threshold: Where ‘Pure’ Starts to Matter

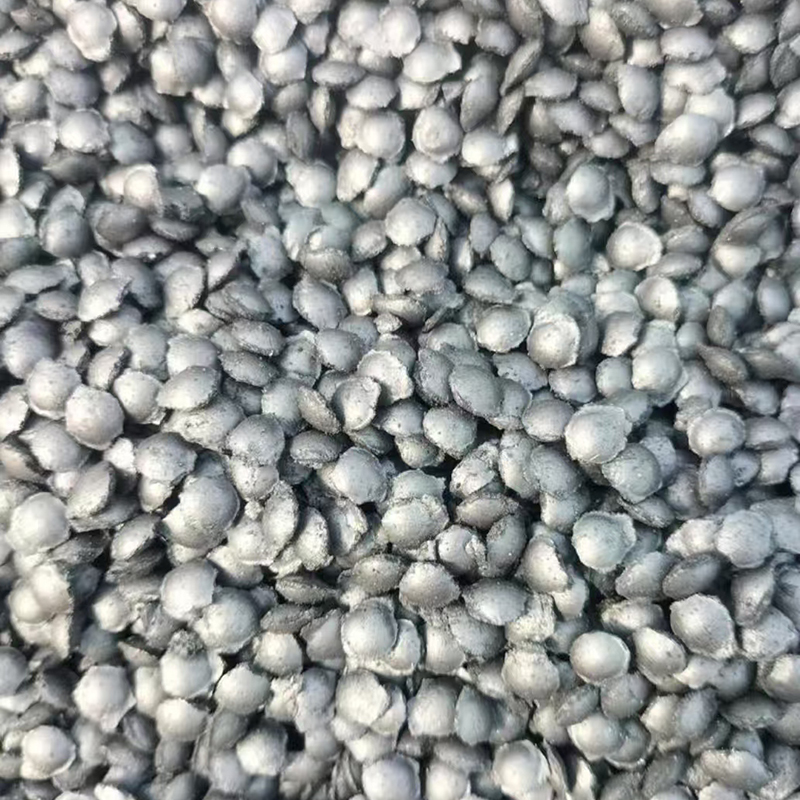

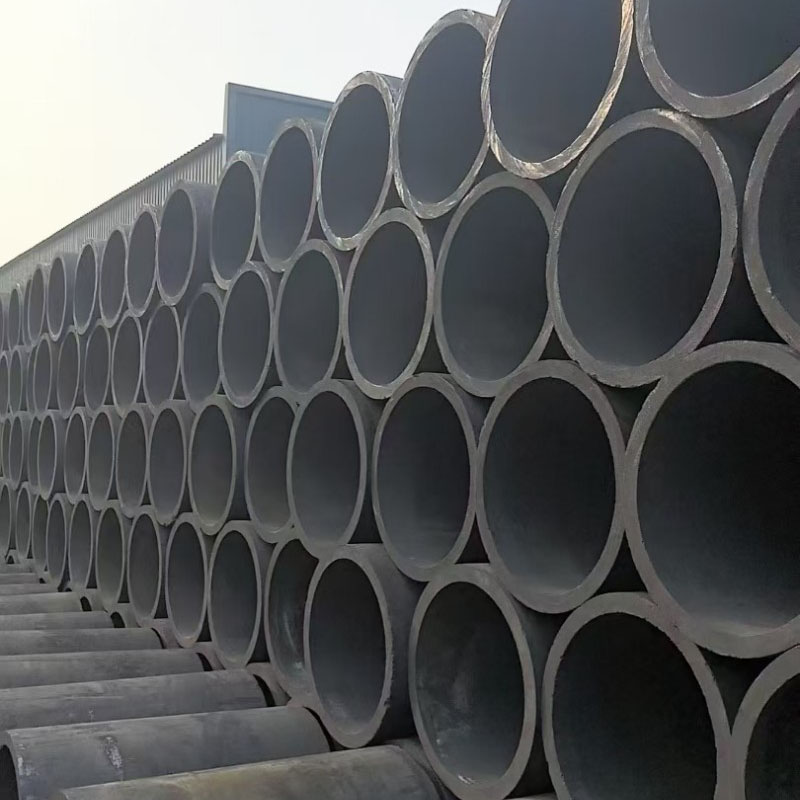

Not all coal tar is created equal. The stuff that gives the whole category a bad name is often crude or lightly processed material. When we talk about pure refined coal tar, specifically for industrial applications, we’re referring to a product that’s undergone significant distillation and treatment to remove volatile, low-boiling fractions and concentrate specific aromatic compounds. The key is the removal threshold. A product like the high-pitch binder from a supplier with deep material expertise—say, Hebei Yaofa Carbon Co., Ltd., which has been processing carbon for over 20 years—is a world apart from generic, unrefined tar. Their focus on consistent, high-grade carbon additives and electrodes necessitates a feedstock with predictable properties. This level of refinement reduces the variability and the concentration of the most problematic light-end components, which is the first, non-negotiable step toward any potential ‘eco-friendly’ claim.

Where the rubber meets the road is in substitution. One of the most tangible ‘eco-friendly’ arguments is when refined coal tar pitch acts as a binder in carbon anodes for aluminum smelting or in graphite electrodes. The ‘friendly’ part is comparative. If the alternative binder is derived from a fresh petroleum stream, the argument is that using a by-product of steel production (coal tar) is a form of industrial symbiosis that adds value to a waste stream. It’s not ‘clean’ in an absolute sense, but it can be more resource-efficient on a system level. The carbonization process in electrode manufacturing also locks a significant portion of the carbon into a stable matrix, reducing potential emissions during the product’s use phase compared to less stable binders. It’s a lifecycle calculation, not a headline.

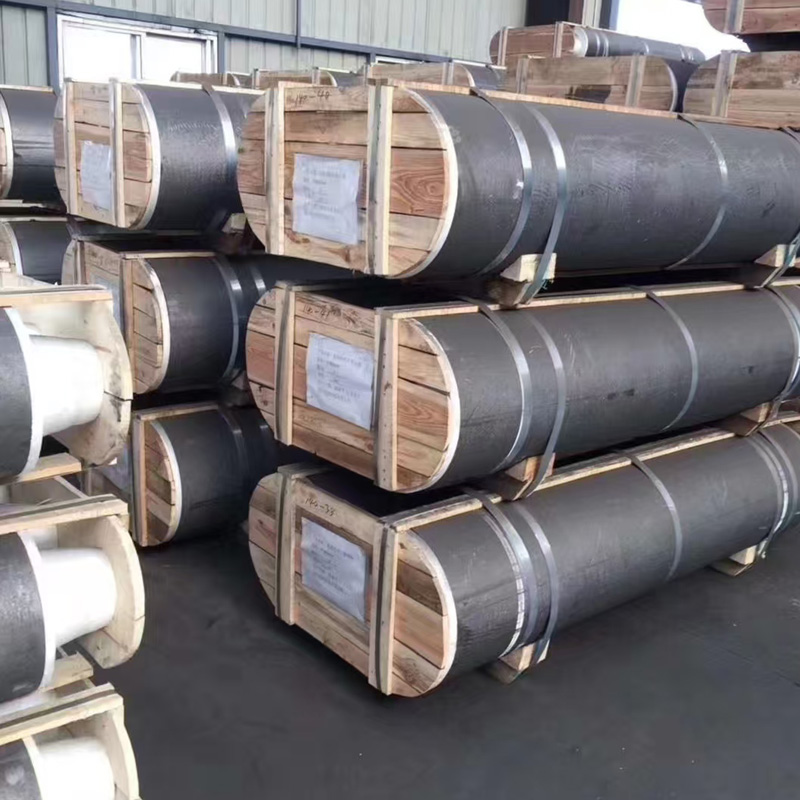

I’ve seen projects stumble by ignoring this threshold. A client once wanted to use a cheaper, semi-refined tar for a specialty carbon product, lured by the lower upfront cost. The inconsistency in viscosity and coking value led to massive production rejects, energy waste in recalibrating furnaces, and ultimately, a contaminated batch that became a disposal liability. The total environmental and economic cost far outweighed the initial savings. That experience cemented for me that ‘pure’ and ‘refined’ aren’t marketing fluff here; they are prerequisites for efficiency and waste minimization downstream. You can’t talk about environmental applications if your base material is unstable.

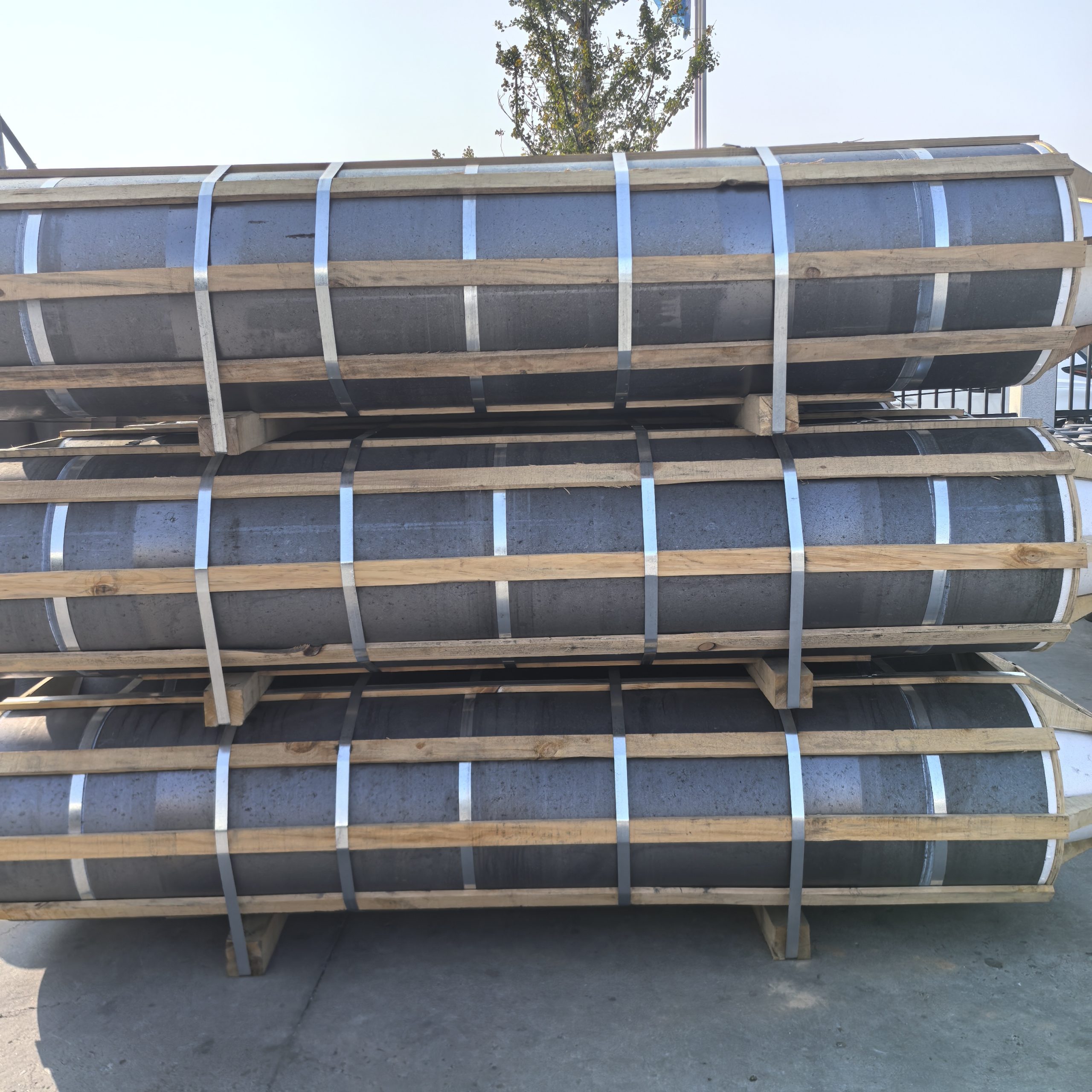

Niche Applications: Where the Argument Holds Water

Beyond large-scale electrode binding, there are niche areas where the properties of refined coal tar are genuinely hard to replace with a currently available ‘greener’ alternative. Think specialized carbon composites for aerospace or high-performance sealing materials. In these cases, the performance requirement—extreme thermal stability, specific conductivity, impermeability—is so stringent that the carbon footprint of a failure (a part that doesn’t meet spec and must be scrapped, or a seal that leaks) dwarfs the footprint of the binder material itself. Here, the ‘eco-friendly’ angle is about durability and longevity in a high-stakes application. Using a subpar binder could mean a component lasts 5 years instead of 20, necessitating frequent replacement and all the embedded energy and waste that entails.

Another area worth a look is in controlled, high-temperature processes for carbon material production itself. A company like Hebei Yaofa Carbon, with its focus on UHP graphite electrodes, is essentially in the business of transforming binders into pure, crystalline carbon structures. In their furnaces, under precise conditions, the volatile matter from the refined pitch is captured and often used as a secondary fuel source for the heating process, creating a closed-loop energy recovery system. The end product, the graphite electrode, is inert and critical for electric arc furnace steelmaking, which is itself a more sustainable path compared to traditional blast furnaces. You can follow this chain on their site at https://www.yaofatansu.com—it’s a good case study in industrial integration. The eco-benefit is indirect but real: enabling more efficient steel recycling.

We also experimented with using ultra-refined fractions as a precursor for synthetic graphite in batteries a few years back. The theory was sound: a dense, highly aromatic feedstock could yield a good graphitic structure. The practical failure was purity. Trace metal impurities, even at ppm levels, that are tolerable in a steelmaking electrode are catastrophic for a lithium-ion battery anode. The purification cost to remove them erased any environmental or economic advantage over petroleum coke. It was a sobering lesson that ‘refined for one industry’ does not mean ‘refined for all.’ The application defines the standard.

The Inevitable Sticking Points: Emissions and End-of-Life

No discussion is honest without confronting the hard parts. The primary environmental challenge with pure refined coal tar remains the handling and initial processing emissions. Even refined, it contains PAHs. During mixing, forming, and the early stages of baking, fume capture is absolutely critical. I’ve visited plants where this is managed with state-of-the-art scrubbing and thermal oxidizers, turning potential pollutants into CO2 and water vapor—a trade-off, but a controlled one. I’ve also seen older facilities where the fugitive emissions are palpable. The ‘eco-friendly’ potential of the application is entirely contingent on this operational rigor. The binder itself isn’t friendly; the engineered system around its use can be.

End-of-life is the other elephant in the room. A carbon anode is consumed in the aluminum pot. A graphite electrode is gradually oxidized in the EAF. But what about carbon composites or specialty products at the end of their life? They’re largely inert carbon, so landfilling is low-risk from a leaching perspective, but it’s still waste. Recycling these materials back into a high-value carbon stream is technically challenging and not yet economical. This is a major gap in the sustainability narrative. The best current argument is that these materials enable long-life, high-efficiency applications, delaying that end-of-life moment for decades. But we need better solutions for ultimate disposal or, ideally, circular reuse.

This is where the industry dialogue needs to go. Instead of vague claims, the focus should be on transparent data: the specific PAH profile of a refined product versus a crude one, the energy recovery rates in modern baking furnaces, and the total carbon balance of a refined tar-based product versus a virgin-alternative-based product. It’s messy, application-specific data, but it’s the only thing that moves the conversation beyond marketing.

Regulatory and Perception Hurdles

Even if the technical case for a lower-system-impact can be made in certain uses, the regulatory and public perception framework is often a blunt instrument. In many jurisdictions, ‘coal tar’ is a trigger word, lumping the refined industrial binder in with creosote-treated railroad ties or old pavement sealants. This creates a barrier to adoption, even for engineers who see the performance benefit. Navigating this requires meticulous documentation, safety data sheets that clearly differentiate the product, and often, third-party verification of emissions profiles during use. It’s an added cost and complexity that any project manager has to weigh.

From a sourcing perspective, this is why dealing with established manufacturers matters. A company with 20 years in the game, like the one mentioned earlier, has had to adapt its processes and documentation to meet evolving standards. Their product consistency isn’t just about quality; it’s about generating reliable data for environmental and safety compliance. When I specify a material like this, I need to know its batch-to-batch behavior not just for my process, but for my environmental permit. An unreliable supplier here doesn’t just risk my product; they risk my operating license.

The perception hurdle also stifles innovation. It’s harder to secure R&D funding to improve the environmental profile of a ‘coal tar’ product than for a bio-based alternative, even if the bio-alternative has its own hidden land-use or processing impacts. This is a reality of the field. The most pragmatic path forward is to continue optimizing within the established, high-value, performance-critical applications where the material is essential, and to be brutally honest about its limitations elsewhere.

Conclusion: A Tool, Not a Panacea

So, is pure refined coal tar eco-friendly? It’s the wrong question. It’s a specialized industrial material with a complex profile. In specific, controlled applications—primarily as a high-performance binder in carbon and graphite products where it enables resource efficiency, waste stream valorization, and long-life performance—it can be part of a more sustainable industrial system. Its ‘green’ credential is entirely contextual and systemic, never inherent. The refinement process is a prerequisite, and the operational controls during its use are what make or break any environmental benefit.

The real-world experience, from failed experiments with battery materials to seeing integrated energy recovery in electrode plants, shows a clear divide. Where it’s used as a drop-in replacement without understanding its specific behavior, it fails. Where it’s integrated into a well-engineered, closed-loop process with full emissions control—like in the production of high-grade electrodes for electric steelmaking—it finds a justified, and arguably optimized, place in the material world. The goal shouldn’t be to rebrand it, but to apply it with precision, honesty about its trade-offs, and a relentless focus on minimizing its impact from cradle to grave. That’s the only kind of ‘friendly’ that holds up under scrutiny in this industry.